Background

Enteric fever is a potentially life-threatening infection. It includes typhoid fever (caused by the bacterium Salmonella Typhi) and paratyphoid fever (caused by the bacterium Salmonella Paratyphi A, B and C). These bacteria only infect humans, and humans are the only reservoirs. Transmission of the infection is by the faecal-oral route (through ingesting food or water that has been contaminated with faeces of an infected person).

It is a disease of poverty because it is usually associated with a lack of clean drinking water and poor sanitation. The disease continues to be a public health problem in many lower- and middle-income countries in Africa, the Americas, South-East Asia and the Western Pacific regions.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), every year an estimated 11–20 million people develop enteric fever and between 128 000 – 161 000 people die as a result. In countries endemic for enteric fever (endemic meaning the constant presence of a disease in a population within a geographic area), children aged 5 to 15 years of age are typically at highest risk for disease and children under 5 years of age are at the highest risk of death.

Of concern is that the global phenomenon of urbanisation (leading to overcrowded populations and inadequate water and sanitation systems) and climate change (leading to flooding events and water shortages) are poised to increase the global burden of disease. Increasing antibiotic resistance and the recent emergence of extremely drug-resistant enteric fever is making it easier for typhoid to spread and more difficult to treat. Safe and effective typhoid vaccines are available, and the WHO recommends that countries with very high burdens of disease or high burdens of antibiotic resistant S. Typhi include typhoid vaccination in their vaccination programmes.

The disease

The symptoms of enteric fever are nonspecific and can resemble many other infections. The most characteristic symptom is a high fever which is usually prolonged, and other symptoms include fatigue, headache, nausea, abdominal pain, and constipation or diarrhoea. Severe disease may occur, and can lead to severe complications which can be fatal.

The diagnosis is usually made by isolating the bacteria from a blood sample (blood culture); there is no reliable rapid test.

Even when a person’s symptoms have resolved and they have completed treatment, they may still harbour bacteria which continue to be shed in their faeces; these persons are called carriers. About 10% of persons who have had an episode of enteric fever intermittently shed bacteria in their faeces for several weeks after infection (convalescent carriers) while up to 4% of those infected become chronic carriers who shed bacteria in their faeces for more than a year. All carriers can spread infection to others when their faeces contaminate food or water. Carriers are very important as reservoirs of infection in endemic countries and cause ongoing transmission in their communities.

Enteric fever is readily treatable with antibiotics, and most patients recover without complications. However, the fatality rate for patients with severe disease who develop serious complications can be up to 30%.

The prevention and control of enteric fever

The measures to prevent and control enteric fever have long been known, and proven to be very effective. They include:

- Water and sanitation infrastructure: safe drinking water and improved sanitation

- Public health measures: correctly diagnosing and treating cases, finding and treating carriers

- Food safety

- Health education: handwashing, food safety practice

- Vaccination: the WHO recommends that countries with very high burdens of disease or high burdens of antibiotic resistant S. Typhi include typhoid vaccination in their vaccination programmes. Typhoid vaccination can also be one of the tools used for controlling outbreaks, along with providing safe water and improved sanitation and other public health measures.

Enteric fever in South Africa

South Africa is endemic for enteric fever caused by Salmonella Typhi, although the prevalence of disease is much lower than most other countries in sub-Saharan Africa. It is a Notifiable Medical Condition, meaning that all confirmed cases must be officially reported to the Department of Health. However, reported cases significantly underrepresent the true number of cases. The likelihood that enteric fever cases are identified and diagnosed depends on many factors, including how ill the patient is, how aware of the disease healthcare workers are, whether blood culture tests are done, and how accessible laboratory testing for blood cultures is. Blood culture tests are not performed at all levels of health care and are not a routine investigation in many South African healthcare settings; blood culture tests are usually performed only for selected patients who are admitted to hospital. This means that many cases of enteric fever are likely missed across the country, especially those cases with milder disease as well as cases in areas of the country where the necessary laboratory testing is not readily accessible.

The number of reported enteric fever cases in South Africa has declined over the last few decades, and larger outbreaks have become less common. The most recent large outbreak occurred in Delmas in 2005, with over 2900 cases.

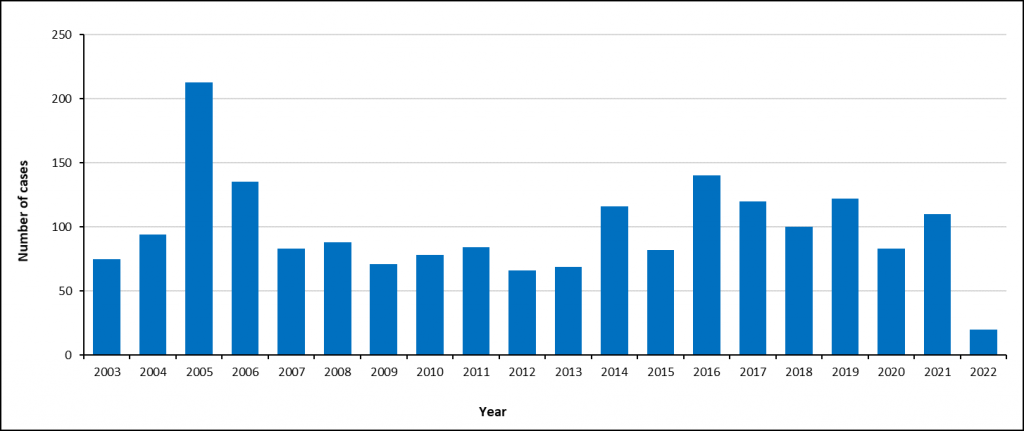

After the Delmas outbreak in 2005, the number of enteric fever cases in South Africa has remained stable with less than 150 cases per year (an average of 97 cases per year) – Figure 1.

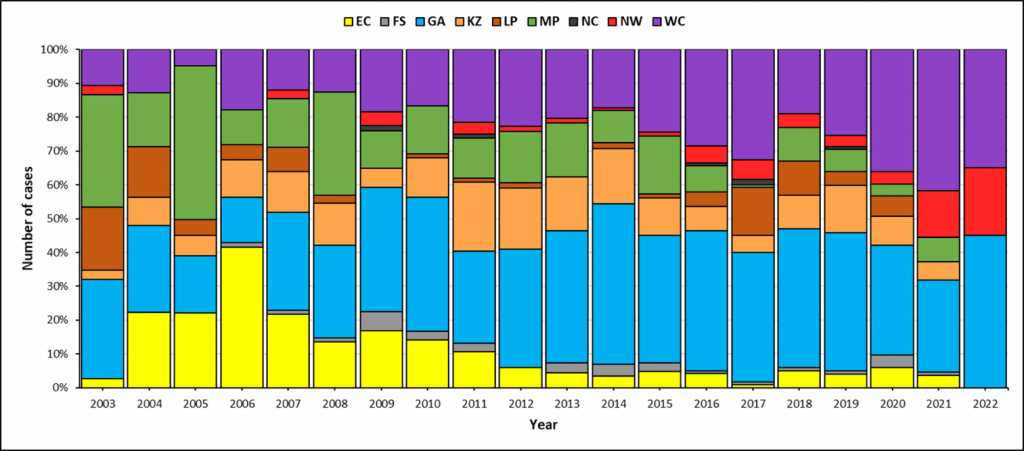

Over the past decade (since 2012), Gauteng Province usually reported the most cases per year followed by Western Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga provinces (Figure 2).

Clusters (small localised outbreaks) of enteric fever in Western Cape and North West provinces

During 2020 and 2021, although the total number of enteric fever cases across the country was similar to previous years (83 cases in 2020 and 110 cases in 2021), there was a relative increase in the number of cases reported from Western Cape and North West provinces (Figure 2). Through the use of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) analysis of S. Typhi isolates referred to the Centre for Enteric Diseases t NICD, we identified clusters (small localised outbreaks) due to different ‘strains’ that were responsible for the increased case numbers in these two provinces. WGS data are investigated using core genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST), which analyses 3002 genes to assess genetic relatedness. A cluster is defined as a group of S. Typhi isolates that on cgMLST analysis differ from each other by ≤5 alleles – this means that they are highly genetically related.

In Western Cape Province there are three clusters, each located in a different district (City of Cape Town Metropolitan, Cape Winelands and Garden Route) and in North West Province there is a cluster in Dr Kenneth Kaunda District. Although the first cases in all four clusters occurred in 2020, the presence of clusters in the respective districts only became evident in 2021 when additional cases were linked through cgMLST analysis. The number of cases in each cluster is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Clusters of S. Typhi in South Africa, January 2020 – January 2022*

| Province | District | Number of cases | Date of first case | Date of most recent case |

| Western Cape | City of Cape Town Metropolitan | 14 | November 2020 | January 2022 |

| Western Cape | Cape Winelands | 11 | July 2020 | May 2021 |

| Western Cape | Garden Route | 12 | August 2020 | December 2021 |

| North West | Dr Kenneth Kaunda | 16 | November 2020 | December 2021 |

*The results of WGS and cgMLST analysis are still pending for several isolates from cases detected in Western Cape and North West provinces during January 2022, so case numbers may change as these results become available.

The relevant provincial and district departments of health are aware of the clusters, and outbreak investigations are ongoing. Contamination of municipal water is extremely unlikely to be the source of infection in any of these clusters, due to the demographics of the cases (including their age profiles, places of residence, source(s) of drinking water and access to improved sanitation) and the scale (each cluster having fewer than 20 cases which stretch over a period of 2 years). It is very likely that there are complex chains of transmission within the respective communities, mostly due to the presence of unrecognised cases and carriers who serve as reservoirs of infection and lead to ongoing transmission. This makes it challenging to investigate and pin point source(s) within the communities.

Healthcare workers countrywide should be more aware of enteric fever, so that cases can be detected and treated appropriately.

Preventive measures for the public include:

- Hand hygiene. Wash hands with soap and safe water before eating or preparing food, and after using the toilet or changing a baby’s nappy.

- Food safety practice. Follow the World Health Organization’s five keys to safer food: keep clean; separate raw and cooked; cook thoroughly; keep food at safe temperatures; and use safe water and raw materials.

- Using safe water. If people are concerned about the quality of water they use for drinking and cooking, then it is recommended to treat the water first by boiling it (place water in a clean container and bring to a boil for 1 minute) or treating it with household bleach (add 1 teaspoon of household bleach (containing 5% chlorine) to 20-25 litres of water, mix well and leave it to stand for at least 30 minutes before use).